The last day of May was warm when geology professor Dr. Elizabeth Petrie and 10 students set out to start the third week of Western Colorado University’s monthlong Geology Field Camp. For some students, it’s the last hurdle to clear before they get their diploma. But for all of them, it’s a chance to get the field experience they’ll need to become geologists.

“When we discuss things in the classroom, or work on geologic problems in the lab, it’s great,” Petrie said. “But being outside, collecting their own data and making those connections without their textbook in front of them. It’s a great way to learn, and students build confidence in their skills.”

Throughout their time at Western, these students, often as a group, have spent many days on mountains or in canyons identifying rocks and the geological processes that formed them. Field Camp is their final exam.

They started the day beside a small reservoir in a mountain valley, where Hot Springs Creek runs along the base of a towering bulge of cooled magma known as Tomichi Dome. In front of them, above 9,000 feet, alpine meadows hid a complex history of upheaval and erosion, revealed in cliffs, outcrops, and hogbacks.

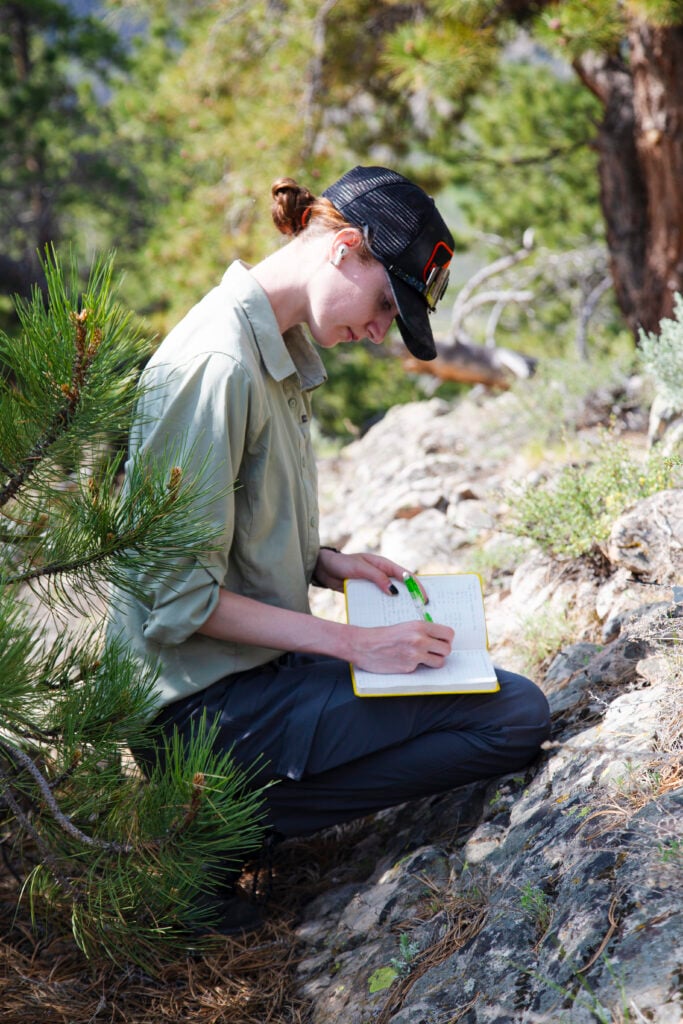

To the uninitiated, it’s a fun jumble of rocks to look at or climb on, but otherwise seems unremarkable. To the students, however, it’s all part of a puzzle they’re trying to piece together. With the observations and measurements they’ve collected, each of them will create a geologic map of an area two miles square, with every fold and rockslide identified.

“It’s fun. This is why we joined the program,” student Sawyer Greer said of the research. “We do it to be in the field.”

Last semester, Petrie and her fellow faculty members led students on excursions doing field research all over the West, helping them gain a geologist’s view of the landscape. Here’s a look at where they went.

Basins and Ranges

In April, thirteen students and four geology faculty – Petrie, along with Drs. Ryan King, Holly Brunkal, and Brad Burton – loaded up the vans and headed south. Throughout their weeklong journey, they stopped at interesting and important geologic features along their route through the Rio Grande Rift, through the southern Basin and Range, and into the Permian Basin of West Texas.

By the time they got to Ernst Tenaja in Big Bend National Park, they had learned to take detailed field notes in the Pine Canyon Caldera, create geologic maps at Apache Gap, and interpret stratigraphic columns and cross-sections in the Guadalupe Mountains to better understand the region’s geologic processes and history.

The trip, made possible with the support of Western’s Department of Natural and Environmental Sciences and its faculty, along with the National Park Service, also coincided with an excursion organized by the Petroleum Structure and Geomechanics Division (PSGD) of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG), which invited the Western group to join their annual excursion.

“Students were able to spend the day with working structural geologists on a trip led by experts in the field. It was an incredible opportunity for both students and faculty,” Petrie said. “Students were able to meet geology experts on the rocks – there is nothing that can compare to that.”

A journey back in time

In July, Geology student Abby Sawicki spent five days rafting through the Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area with Drs. Petrie and King, where they worked to describe the contact deep in the canyon where Jurassic sedimentary rocks meet the much older metamorphic rock of the Precambrian basement.

They studied outcrops and collected samples to learn how the mineral composition and structures in the rocks might influence the movement of fluids deep underground.

According to Petrie, “induced” earthquakes have been observed in the Precambrian basement up to 10 km from deep injection wells, where subsurface injection is used to store chemical waste, produced water, or carbon dioxide, highlighting the need to better understand how these types of contacts influence fluid movement.

“With subsurface injection being used for disposal, it’s important to inject deep enough to prevent waste from interacting with sources of drinking water and the atmosphere and at rates and pressures that won’t induce earthquakes,” she said. “This analog data is crucial for understanding rock strength, mechanical properties, and the potential for rock failure in deep injection scenarios, and we are lucky to have access to these exposures.”

The excursion into the Gunnison Gorge was a logistical feat, requiring the coordination of several people and institutions. The work, which was done in conjunction with Dr. King’s ongoing research in the area, required sampling permits from the Bureau of Land Management because it took place in the National Conservation Area.

Then, to access the interior of the gorge, the team needed the skills of seasoned raft guides. Western’s own Tara Allman, Bob Jones, and Tim Jones volunteered to navigate the river between sampling locations. Without the BLM’s cooperation and their guides’ willingness to help, Petrie said, “We would not have had this opportunity.”