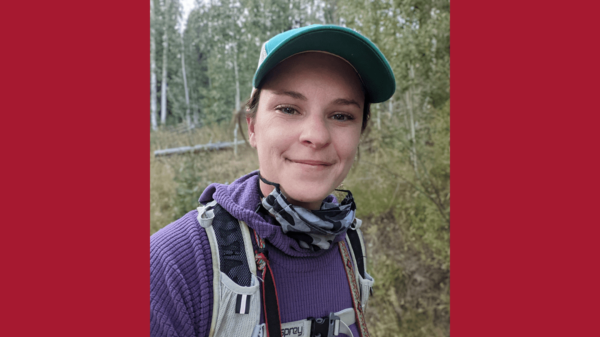

Dr. Suzanne Taylor’s quest to find new worlds in the final frontier.

There might be as many as 400 billion stars in our galaxy. On a clear, moonless night, it’s possible to see a few thousand, or about 0.000001% of the total. So what are the chances that just one star out there will have a habitable planet we can see? Dr. Suzanne Taylor is trying

to find out.

Taylor, a physics professor at Western Colorado University, is part of a network of scientists involved in TESS, or the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, which is an MIT-led NASA mission aimed at learning more about planets that orbit stars outside our solar system. Ultimately, they hope to find other rocky planets in the habitable zone where conditions might be right for liquid water, a crucial ingredient for life as we know it.

Launched by NASA in April 2018, TESS is a space telescope that scans nearly the entire sky, examining the brightest stars for evidence of planetary transits. When a planet crosses in front of its host star, it causes a temporary dimming of the star’s light, and TESS is there to see it.

As a co-investigator on the TESS team, Taylor steps in to confirm those observations, collaborating with leading astronomers worldwide, analyzing data to identify new exoplanets, and studying their characteristics. It’s work that is instrumental in advancing what we know about distant worlds and the potential for life beyond our solar system.

From one opportunity to the next

Taylor grew up in Anchorage, Alaska, where, during the winter months, she had a great view of the night sky all day long. She had a small telescope 4 and always loved the stars, dreaming one day of becoming an astronaut. But in high school, she realized she would never meet the physical requirements for going to space and would need to find another way to pursue her passion for the cosmos.

In graduate school at the University of New Mexico, where she was pursuing a PhD in astronomy, Taylor was introduced to the idea of exoplanets. However, it wasn’t until she was offered a faculty position at Western in 2013 that she decided to pursue the search for distant worlds.

The Gunnison Valley Observatory (GVO), just a few miles south of campus, became a home away from home for her. Sitting on the edge of town, surrounded by tall berms shielding the town lights, it was a dark and quiet place where she could do her work.

But while the impressive 30-inch telescope at the Observatory, with its cast iron mount, giant gears, and domed housing, is perfect for public viewings, it isn’t quite refined enough for research, where keeping a star in view as it traverses the sky is imperative. So Western bought a research-grade telescope to help with her research, and GVO stepped in to provide a mount and a building to house it. After the main components were assembled, Western students helped add technology that would bring the new telescope online so it could be remotely operated and track a single star for hours across the night sky.

“By mid-summer last year, we were able to get that telescope and the roll-off roof observatory remotely operable. So I could sit in my living room at home [and do research],” Taylor said. “It was great. We had a system where one person would get it up and running, and another person would collect the data, and then another person would then go back to do the shutdown.”

Reaching for the stars

For students in many majors, from physics to engineering, the search for exoplanets is a fascinating way to dip a toe in the inky black, star-studded world of astronomy. It doesn’t require an advanced degree and allows students to take the theoretical knowledge they’ve learned in the classroom into the field, where they can help do cutting-edge science.

“Exoplanets made a lot of sense in terms of working with students because it’s something students can get excited about. There are projects that students can be involved in,” she said. “A student who has some physics background or some astronomy background is able to get into it and actually do some meaningful stuff.”

The TESS project also gets students off campus and into the community as volunteers at GVO, where the public can go on summer weekends to see the stars and hear people who are passionate about astronomy pick out constellations and talk about the cosmos.

One day, while Zeth Palmer was out enjoying the trails at Hartman Rocks, he looked out over his surroundings and saw GVO tucked down behind its berms beside a nearby neighborhood. Curious, the Western senior double-majoring in physics and mathematics started asking around campus, hoping to find out more. Soon, he was pointed to Taylor, who was happy to help, introducing him to other board members and signing him up to operate a small telescope during weekly public viewings.

Before long, his knowledge and interest led to a collaboration with GVO board member Rob Brown on a radio telescope, which is designed to detect radio waves emitted by distant cosmic sources, as opposed to the light waves studied by traditional optical telescopes.

The experience has added a layer to his education that undergraduates at most universities won’t have, and Palmer sees it as giving him a leg up after graduation when he enters a competitive field of job-seekers and graduate students.

“Without Dr. Taylor and GVO, I would not have ever conceived the radio

astronomy project,” Palmer said. “Other professors have advised me to use the radio telescope as my physics capstone project. Although that was not my original intent, what an opportunity!”

Begging the Question Why

On a July evening, just as the first stars started to show through a break in the clouds, Taylor stood in her small shed at GVO with the roof rolled off to one side. She scanned a spreadsheet on her laptop for a candidate that showed an anomalous dimming during previous observation and punched in the coordinates. The telescope

mounted on a stand behind her hummed to life and rotated toward a star more than 36 light years away named Arcturus.

“There’s a lot of stars out there, a lot of galaxies. Most stars probably have planets, and habitable planets are fairly likely,” she said. “It would seem like it would be kind of ridiculous that there would only be life on one planet. So, life somewhere in the universe is very likely, and I think intelligent life is also reasonably likely. But, it just seems like the numbers are huge, and the odds are pretty good.”

Does that mean she’s looking for aliens or believes aliens are looking for us? No. “The scales are just huge,” she said. But the search for exoplanets is not just about finding new worlds, and certainly not about aliens; it’s about understanding our place in the universe. And each discovery brings us one step closer to answering the age-old question: What makes us special?

Author: Seth Mensing