The leaves in the forest here hang limp and motionless as the dry season comes to a close in this far corner of Belize.

Soon, the rain will start, and the roads will become impassable. But even now, ‘dry’ is a relative term. Just standing in the dense air is enough to make a huddle of students sweat through their shirts while they wait for the last members of their group to walk to the top of a low hill. For weeks this season, they’ve been digging pits here, searching for clues about an ancient past. Now, their time is almost over. After ten seasons spent working in this area known as the Med Trail Site, Dr. David Hyde and his team have just two days left before they must move on.

Dr. Hyde earned his stripes as an archeologist not far from here while he was an undergraduate student at the University of Texas at Austin. His very first class there was taught by Dr. Fred Valdez, who holds the only permit to conduct archeological research in the 254,000-acre 4 Rio Bravo Conservation and Management Area (RBCMA), established in 1988 to protect the area’s many ecological and archeological treasures. The summer after the course ended, a young Dr. Hyde signed up for Dr. Valdez’s field school. “I sold pretty much everything I owned and came down here,” Dr. Hyde said. “I remember being about two weeks into the program … and just kind of stopping, and I turned to my friend Erica, and I said, ‘I’m going to do this for the rest of my life.’” He’s been back nearly every summer since.

In 2008, he was tapped to direct the Medicinal Trail Hinterland Communities Archeological Project, as this dig is officially known. Shortly after joining the faculty at Western in 2011, he brought his first Mountaineers here. And still, after ten years of digging by more than 70 students, the Med Trail Site continues to reveal new secrets.

Unearthing Rituals of the Past

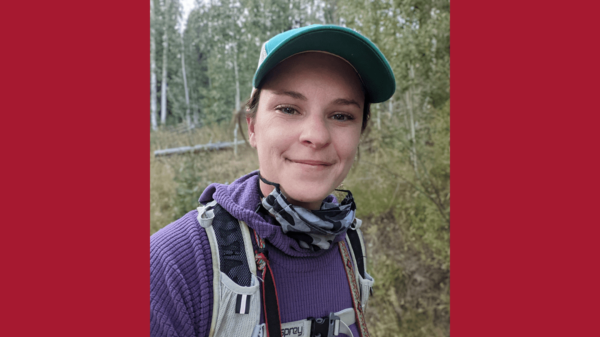

Hunched over in a shallow pit, Ashlyn Grogan (Anthropology ’24) hopes to find some of those secrets. She stabs the dirt carefully with a trowel and sweeps the loosened soil into a dustpan with a small wicker broom. She’s exposed two layers of carefully arranged limestone blocks, worn but clearly shaped by skilled hands, and continues to dig toward bedrock. The dirt she removes is sifted through a screen that catches chunks of limestone, bits of pottery, and occasionally a flake of obsidian. Anything larger than a quarter goes in a white cloth bag for cleaning and analysis. The further down she digs, the more she finds. Eventually, the pieces of pottery shards fill up so many artifact bags that these seemingly simple finds add up to a valuable discovery for students learning about a long-vanished culture.

Dr. Hyde believes the presence of so much pottery at the base of a wall isn’t a coincidence and instead suggests some kind of termination ritual played out as the people who occupied the area were preparing to leave. In the ancient Maya’s animistic view of the world, even the clay their pots were made from contained a vital life force. So, as the Maya who once lived here were getting ready to relocate from the Med Trail Site to someplace new, they would have broken the pots to free the life contained within them.

Just up the hill, another pit contains the remains of another wall. But this one is even more unique. It’s curved in a way that was uncharacteristic of the Maya who lived here, during what’s known as the Classic Period (200-900 C.E.). Almost all Maya construction from that time was arranged according to the cardinal directions: north, south, east, and west. Rounded corners or bowed walls were quite rare. Even more intriguing, beside the wall, students found what’s known as a god pot, or face pot, which is an egg-shaped ceramic vessel a little over a foot tall. An appliqué of clay covered the surface and was used to fashion the face and ears of a Jaguar, the god of the underworld.

At the very top of the Med Trail Site’s terraced hillside, Troy Brown (History/Anthropology ’23) and Jo Raetzel (History/Anthropology ’21) are covered in sweat and white limestone dust after finding the remains of yet another wall. It’s harder to make out than the others; many of the blocks have disintegrated or shifted from their original position, pushed by time and intruding tree roots. But Dr. Hyde has seen something similar before and directs his students to excavate along the face of the wall to the south until the blocks eventually regain their shape. There, they uncover a threshold at the base of what looks like a doorway. Pointing to round sockets carved in stone where posts once stood, Dr. Hyde said that above this, the Maya would have built a wooden structure. But all that’s long gone now.

Anything beyond the threshold or beneath the ground in this part of the dig will remain a mystery, at least for now. The plan was always to work on the Med Trail Site until the end of this season and move on to other areas of the RBCMA. In their time here, students uncovered centuries-old structures and the site of a termination ritual. They found chert tools for shaping the softer limestone into blocks, mano stones for grinding grain, a rare god pot, and even a tall, narrow monument known as a stela, complete with offerings of incense and a beautiful jade pendant. But now, before Dr. Hyde and the students leave the site for the last time, they refill all the pits and

reclaim the area, hoping to protect what remains from looters and preserve it for posterity.

Exploring the Unknown

Whether the Med Trail Site was a religious site or a marketplace, no one knows. So far removed from the past, stone artifacts and hypotheses are all the researchers will ever have. In a place with more biodiversity than nearly anywhere else on the planet, the nutrients in fallen organic material are in high demand by new growth, which leaves the soil shallow and acidic. As a result, clothes, sandals, dolls, wooden toys, or anything not made of stone or pottery disintegrated long ago. Even bone is often ground to powder as the soil swells in the rainy season and compacts in the dry season.

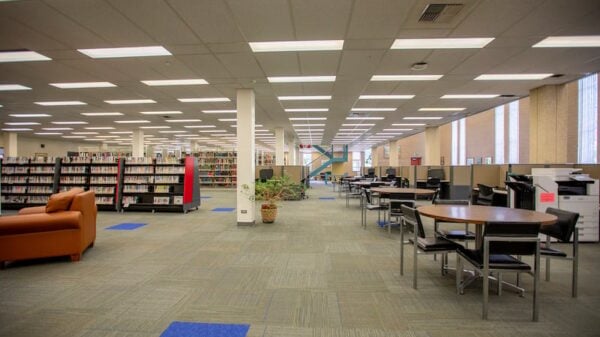

At the end of each day, the bags of pottery shards, obsidian flakes, and any other artifacts uncovered during the excavation will go to the laboratory at the field school for cleaning and cataloging. When Dr. Valdez first came to the RBCMA in the early 1990s, the laboratory was the first building he and his colleagues constructed. Since then, the field school has added a dozen small buildings, all built in the same way, with rough-cut lumber and screen.

Field School’s Impact on Students

For many of the students who come here, field school is their first chance to travel internationally, let alone sleep in tents in the jungle. Most haven’t stayed for an extended period in a place without cell service. According to Dr. Hyde, those are some of the things that make this experience so transformative. The close friendships that are forged here are another. “You make incredible bonds with incredible people out here,” Brown, who was on his third month-long trip to field school since 2019, says. “Surviving a month in the jungle creates a connection with people you can’t find in many places.”

Mornings in camp are marked by a cacophony of bird and bug sounds and the hum of a generator, which brings power to the camp at 5 a.m. But sometimes it’s earlier, depending on the needs of the small staff, which consists of a local extended family, who does the cooking, cleaning, and maintenance. The call for breakfast goes out at 6 a.m., just as the smell of scrambled eggs, refried beans, fruit, and fry bread fills the dining hall. In the evenings, after dinner is served and the dishes are washed, students gather there for games or a movie or to listen to a talk given by one of the visiting experts.

On a Tuesday night in June, Mike Stowe, the senior archeologist at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, was giving a presentation on the discovery of ancient human footprints preserved in bedrock that had recently created a media frenzy. Everyone in the room knew the story, and Stowe was a minor celebrity for his association with it. But on this trip, he hadn’t come as a celebrity guest. He came to gather data for a topographic map of the Med Trail Site as a favor to Dr. Hyde. The two had forged a lasting friendship while attending this very field school together in the late 90s. Now, he’d returned as one example of what someone with an anthropology degree could do after graduation and provide students with some advice about how to get started in the profession. For the right candidate, he offered an opportunity or a personal reference.

Other than centuries-old artifacts and hands-on experience, professional opportunities are some of the most valuable things students will find at the field school. Not only are there professional archeologists like Stowe and Talle Hogrefe, the top archeologist for Jefferson County (Colorado) Open Space, but other leading faculty and researchers from top universities eat and mingle with students. After the movie or presentation, there’s a mad dash for the showers before the generator goes off at 9 p.m. and the lights go out. Then, slowly, the sounds of the jungle return.

The Future of Field School

Today, the Med Trail Site is just one of at least 60 Maya sites that have been identified in the RBCMA, most of them untouched. The area’s crown jewel is a settlement named La Milpa, which is the third largest known Maya site in all of Belize, behind the well-known and well-developed sites at Caracol and Lamanai. The Great Plaza at La Milpa is one of the largest public spaces in the known Maya world. It is surrounded by more than 24 courtyards and 85 structures, including four temple pyramids, with the tallest standing about 75 feet above the plaza floor. There’s also a ball court where the famous Maya ballgame was played, several stelae, and dozens of other structures that remain mostly hidden beneath the jungle floor, almost completely untouched by archeologists. No one knows what secrets the ground here holds.

With a chorus of howler monkeys hollering in a nearby tree, Dr. Hyde walked around La Milpa’s Great Plaza holding a stake, imagining the excavations to come. It’s a two-acre opening as flat as a soccer field, with tall, tree-covered mounds on all sides. He turns in a circle on the sun-dappled ground and surveys the space. With a bit of theatrics, he holds the stake above his head and then stabs it in the ground; this, he says, is where a new generation of students, from Western and beyond, will pull on the thread that unravels the veil over La Milpa.

Author: Seth Mensing