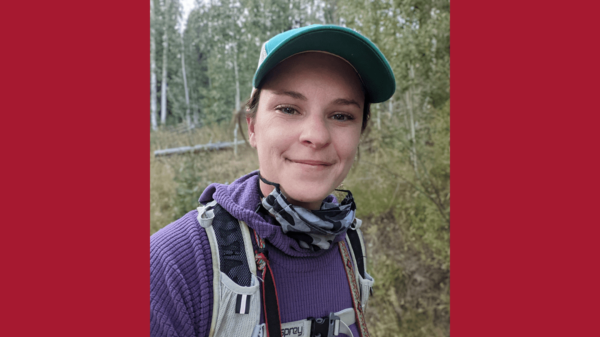

Wynn Martens grew up connected to the land. On her family’s Monument Divide ranch northeast of Colorado Springs, miles of shortgrass prairie rolled out in every direction, and the rhythms of life played out much as they had a hundred years before. Cows mingled with deer and birds as they wandered vast pastures in search of prime grazing. “We were always very conscious about how we grazed, but we did it in a traditional fashion,” she said. “Large pastures with cattle picking what they wanted to eat and revisiting the most desirable plants at their leisure.”

In the summer, after calving season and putting up hay, her father would get the itch to travel the state. The family would pack up and head into the mountains, taking a “family roots” tour that would often pass through Crested Butte, where her great-great-grandfather, Orlando Sylvester “OS” Beardsley, had, staked mining claims on Sheep Mountain in the Crested Butte area, and operated a blacksmith shop in Gothic in the late 1880s. They were memorable trips that left a deep impression.

In college, she went skiing on Crested Butte Mountain with friends, including her future husband, Ryan. The year they were married, the ranch where she grew up was sold and later subdivided. She never went back, uncomfortable with what she’d see there. But the trips to Crested Butte continued. When the couple was ready to buy a vacation home, they knew where it would be. There was just something about the Gunnison Valley that felt like home.

“I remember as the town was creeping this way, how unique it was to have the cattle right up against the community,” Wynn said. “And, at the time, we didn’t have any understanding of what was in the works, who owned what, and how the puzzle pieces fit together. But it was a really unique feature to be able to look down the streets and very frequently see cattle.”

Eventually, after several moves on the mountain and in town, they landed in a quiet neighborhood at the end of Belleview, next to what remained of the old Verzuh Ranch, where the views stretched unimpeded toward Crested Butte Mountain and cows still grazed along the banks of the Slate River.

The Martens think about their impact on the environment a lot. But it’s not just about their own impact. They think about how the systems that support us all impact the land that supports everything else. To them, food production, in particular, seems to be something that can either blend with its environment and even improve it or degrade the land in an unsustainable way. “As a society, we need to understand the impact we have on nature and how nature can help us clean up our messes,” Ryan said.

Humanity has made one of its biggest messes in the atmosphere, where an excessive amount of heat-trapping carbon is changing the Earth’s climate. Healthy plants consume carbon and pull it down under the ground, where it’s stored in the soil. A healthy root system can store a lot of carbon, not only in the roots themselves but in the soil the roots come into contact with. But without healthy plants aboveground, root systems below the ground are stunted, as is that plant’s ability to sequester carbon.

Back on the ranch, Wynn knew the cows had their favorite places, where water was accessible and good grazing was close by. Left to their own, cows will stay where they’re comfortable and return to the easiest grazing as often as possible. Soon, the grass is clipped so close to the ground that it can’t recover before the cows return to clip it again. Root systems suffer. According to data from the Bureau of Land Management, which issues the vast majority of grazing permits on federal land, more than half of the land it manages is in poor health, and two-thirds of that is due to overgrazing.

The Savory Institute is a Boulder-based non-profit that advocates for holistic land management practices that take advantage of the interaction between the ecosystem and the animals it supports. By grazing cattle in a concentrated area for short periods of time and moving them often, ranchers using the Institute’s methods have found that a herd of cattle can mimic the movement of bison and other large ungulates across the landscape, pushing manure and nutrients into the soil and allowing grass to fully regrow before it is revisited. Hooves break up compacted soils and allow rain to soak into the ground. And when cows return to healthy grass, grazing stimulates the growth of roots. These healthier, more productive landscapes provide better habitat for wildlife.

To test what they’d learned at the Savory Institute, the Martens purchased the 40 acres adjacent to their home on Belleview, where they graze between 35 and 50 cows through the summer. Moving the herd between one-acre paddocks once or twice per day has fertilized the ground and allowed the grass to regrow in places that were previously bare. Willows have reestablished themselves along the Slate River, stabilizing its banks. In a place where the ground had been grazed in the traditional way, it was a shining example of just how effective regenerative agriculture and holistic management practices were at bringing new life to a working landscape.

By taking an old practice like ranching and breathing new life into it by looking back to a time before humans controlled so much of the land and its animals, the Martens are hoping to help bring balance to an inextricably entwined ecosystem. “How do you take these landscapes and not just put them back to where they were, but put the mechanisms in place that cause them to be regenerative and let them go so nature can do its job,” Ryan said. “We need to stop behaving like we can actually control such a complex system, like the one that keeps us alive. Trying to control the natural system is a fool’s errand.”

At the heart of regenerative agriculture is an ethic that informs a worldview focused on outcomes deeper than increasing the productivity of agricultural lands, although it still does that. It’s about finding better ways to live on and steward the land. The same grass that feeds a rancher’s cows also feeds insects, elk, and deer, provides cover for small mammals, and is a critical habitat for birds. Beyond the plants and animals, controlling where cattle can and can’t graze and where they can’t allow ranchers to keep cows away from riparian areas and wetlands, where they damage stream banks and eat important plants like willow and alder. “It’s not a sustainability story. It’s not about stopping where we’re at,” Wynn said. “It’s about getting to a place where things get better every year.”

In 2018, the Martens got a boost when the Crested Butte Land Trust convened the Slate River Working Group, bringing together 18 stakeholders, including land managers, local businesses, outdoor enthusiasts, and private landowners, including the Martens. Together, they hoped to find ways of managing their individual lands in a way that preserved the valley’s open space and recreational access without loving the wetlands and wildlife habitat to death. To help provide a conservation perspective, they enlisted Western’s Associate Professor of Wildlife & Conservation Biology, Pat Magee.

The Martens were aware of Western but had no personal connection to the University until then. In Pat, they saw someone who shared their passion and desire to find a way to preserve the natural systems that support life on Earth. Soon, they invited him out to Verzuh Ranch and encouraged him to bring students and do a census of birds on the property. “I think Pat has really evolved our thinking around interacting with and finding balance on the land. He also helped us see what a key indicator species birds are for the health and the biodiversity of the landscape,” Wynn said. “And it’s just been fun to learn what’s out there and the list of species every year just gets longer and longer.” Now, after six years, the list contains more than 90 species of birds.

In Western, the Martens saw an opportunity to partner with an institution that could provide the intellectual and human resources to study each of the many interactions that take place on Verzuh Ranch over a long period of time. They saw a willing collaborator whose interest and vision matched theirs. “We have just been so, so impressed with the quality of the people at that institution, the openness and the collaboration and the willingness to say ‘yes, we will. We want to work through that,’” Wynn said. So in January 2024, they signed ownership of Verzuh Ranch over to the Western Colorado University Foundation so the property could be preserved in perpetuity and serve as an outdoor classroom and learning laboratory where Western’s faculty and students can conduct research and study the many complex interactions that take place there. It’s a gift they hope will lead to real changes in the way we live on the land.

“We needed an educational institution to help [us proceed]. That’s why Western is perfect,” Wynn said. “It’s well-loved. And when you take an institution that’s open and collaborative and wise and rooted in the community, it can be the place that breaks the Tragedy of the Commons.”

Author: Seth Mensing