We’ve turned away from the planet and even our human landscape. If we turned back to that and learned to love all of it, there would be some reciprocal benefit. Why would we hurt something we love? -CMarie Fuhrman

Like an artist in any medium – a painter with a palette, a sculptor with clay, or a musician’s notes on a page – CMarie Fuhrman hopes that her words make you feel something.

The feelings her words illicit might be wonder or awe, shame or indignation. They might make you believe you’ve curled up under a warm blanket or like you just touched a hot pan on the stove. To feel something is to change from one state of mind into another. That’s the journey she wants her words to take you on. It could be a journey we want or a journey we need.

CMarie has always believed in the human capacity to change – for the better with the right stimulus.

It seems, when you listen to her words, that she doesn’t want so much change that the future forgets the past. But enough that the future is better for it. As a Native woman born on the Southern Ute reservation and adopted by first-generation European-American parents, remembering her own past provides her with an identity that can seem as complicated as it is important to who she is. It provides her with a sense of empathy that’s hard to overstate. Through her words, she wants us to empathize, too – with everything. With the cranes that fly from some far-off wintering ground. With 12,000 salmon, and countless more, whose journey upstream was stopped by a dam on a once-wild river. With the people who were forced from their homes by newcomers who saw the land as a “what” and not a “who.”

Building a life with words

Just like her past, her words are central to who CMarie is. Like paints on a palette, there are many, and she uses them carefully when she speaks and writes. She tried to make a life without them once, earning a degree in exercise physiology and working in the field for 20 years. Even there, she was trying to bring about change of a different kind. But a life made with words was never far from her mind. Even as she went through school, working toward her first degree, she was taking writing classes and thinking about her second one. Now, and back then, perhaps, she speaks like someone who is mindful of the words she uses, unafraid of speaking about her convictions, of her ancestors, and of the things that only a poem or a carefully considered essay gives you the license to say. Once, while camped beneath a dam, she was out for a hike, and a poem came to her.

Harmonizing with nature

When you hear her speak or read her writing, it’s clear that CMarie loves the musicality of language. When she wakes up in the morning and walks out of her cabin in Idaho, she greets the trees with the words of her ancestors. To repeat them would take practice. To write them here is barely possible. But they’re beautiful.

“This is the language they speak,” she said. “Of the words the trees have heard most over the last 16,000 years humans have been walking beneath them, these are the words they have heard most often. I learned nimipuutímt (Nez Perce language) when I first moved to Idaho so I could better communicate with the landscape. And having made a community there and learning the 16,000 years of history in that area, you can’t separate the two.”

Navigating complexity

CMarie doesn’t hide from the complexity of the problems she addresses in her writing. So much of the conversation these days consists of trumpeting your values while minimizing those of the other side. But she doesn’t do that. The subjects she thinks about, and writes about, are complex. There is no easy answer, and she doesn’t pretend to offer one.

“Looking at the dam, it’s a beautiful construction. It’s amazing what we can do,” she said. “But then, look what it has done and what it’s still doing to that river and the 12,000 salmon that died in a 24-hour period at the base of the dam.” It’s a hard thing to look at, but she wants you to look. She’s aware of the discomfort her work can cause people, and if she doesn’t actively seek to make people uncomfortable, she certainly doesn’t stop short of it either. That discomfort comes from hard questions. She knows hard questions are where we get important answers.

Amplifying her impact

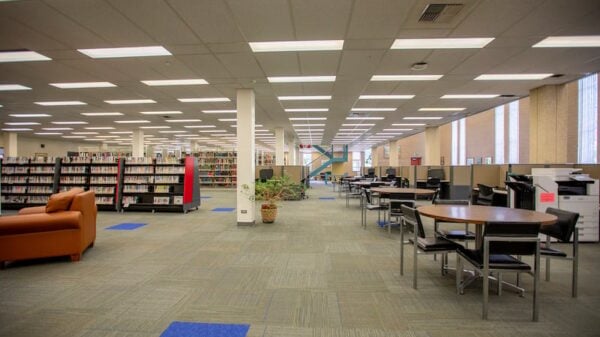

The thing that gives hard questions value, though, is that people want to see them answered. As she continually develops her craft, CMarie keeps finding new ways to share her words so the answers feel more important, more pressing. In her most recent venture, she collaborates with outdoor sound recordist Jacob Job on Terra Firma, a Colorado Public Radio podcast combining CMarie’s words with Job’s sound to create a short, narrated escape. Her latest book Cascadia, which she edited with Elizabeth Bradfield and Derek Sheffield, “brings together art, poetry, and stories holding scientific, sensory, and cultural knowledge … offering any reader a new way of connecting.” As the Poetry Director and Associate Program Director in Western’s Graduate Program in Creative Writing, she shares her passion for words and the tools she’s acquired with students who can take her message and serve as exponents.

For CMarie – whether it’s in a poem, an essay, a podcast, or a lecture hall – the message is always about connection: a connection with a place, with the people, with the past. You can’t love what you don’t feel connected to, and love, she knows, is what will get us to a better future.

“If we were turning our attention and love to place, we wouldn’t be in this crisis,” she said. “We’ve turned away from the planet and even our human landscape. If we turned back to that and learned to love all of it, there would be some reciprocal benefit. Why would we hurt something we love?”